|

Throughout this series of blog posts, I have included tips on what you will need and what the experience is like. But what you seldom read about is what happens to you when you get back.

First of all, you will look at the incoming group of poor sods about to tackle the mountain and will smile knowingly into your beer, not wishing to be them for a single minute. And then you realise that the team who came down the same time we were about to head up were looking at us in exactly the same way. Secondly, your body can have a delayed reaction to the exertion, high altitude and temperature extremes you've gone through. Here are some of the effects we experienced:

Yip – it’s all glamour. But is it worth it? Yes. Would I do it again? No. Am I glad I did it? Absolutely. Go back to day 1 Want to meet other women who like going on hiking adventures? Join Glamoraks.

2 Comments

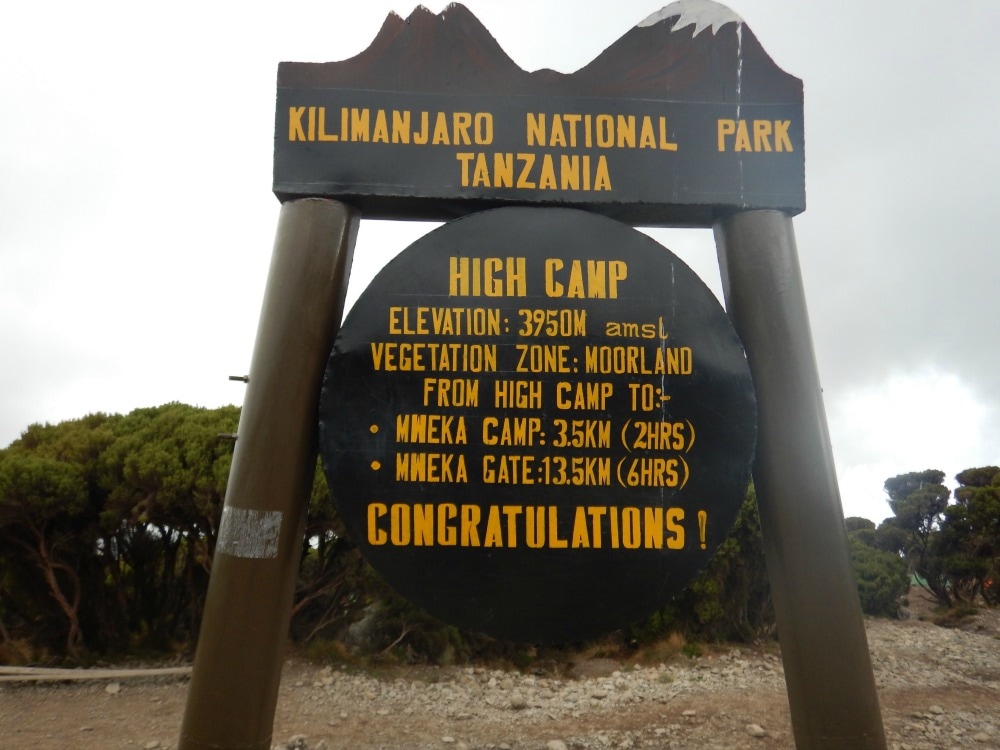

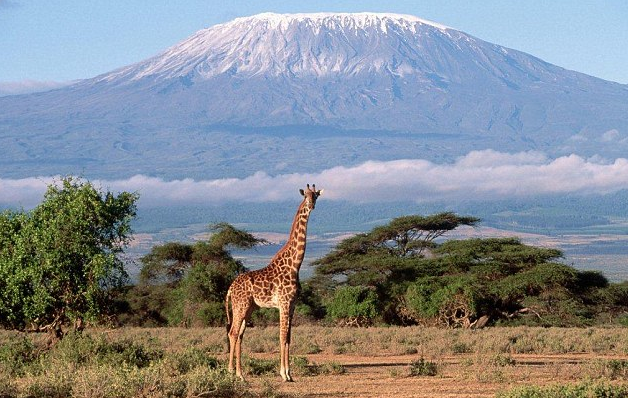

Start height: 3950m End height: 1800m A 6am wake up call by our coffee porter, revealed a gloriously sunny day. The snow covered peak set against a bright blue sky seemed surreal. We’d been there. We’d done it. All the exhaustion of the previous day had gone and we could at last celebrate our success. A brilliant breakfast of delicious (yes, really) porridge was followed by pancakes, fruit and Vienna sausages, which no-one except me seemed to like, so I ate my body weight in them. It was our last time packing up tents, our last time of putting on filthy clothes. There was a spring in everyone’s step and laughter throughout the camp. Donations of kit were made to the porters, some of whom trek up the mountain in ancient crocs with holey socks and thin sweaters. They thanked us by singing and dancing for us again. We all joined in. It’s amazing what a bit of extra oxygen will do for you. We bid farewell to the camp after group pictures and began a long, steep descent. The path started with more rocks to clamber down, which reminded tired legs of the pounding they’d taken the day before. Knees and toes put up a protest, but there is only one remedy – keep walking. We were joined by one of the guides Godfrey, who filled us in on plenty of local plant knowledge, local customs and tales from his portering days when he was required to carry 40kgs on his back, unlike the regulated 20kgs now. We passed through Mweka camp and instantly the vegetation changed from alpine to rainforest. The path was smooth, gently sloping and shaded by trees. I couldn’t help myself – I had to walk fast. In fact I practically ran a good portion of it, just to feel speed for the first time in a week. Over pretty bridges, past incredible trees. The path just went on and on for about four hours. Finally, just as my knees and toes were ready to throw in the towel, the end sign came into view. And that’s when it happened. The feeling that I expected to get at the summit – but didn’t – kicked in. Tears. Lots of them. I’d done it. I’d gone there and back to see how high it was. It’s high. It was hard. But it was absolutely worth it. A celebratory beer and samosa awaited us. The heavens opened in a tropical deluge. But nothing was going to dampen our spirits. We had just conquered the highest freestanding mountain in the world. We’d stood on the roof of Africa. We’d seen the curvature of the earth and watching the sun rise beneath us. We’d pushed ourselves to our limits and survived with a smile on our faces. Thank you Kili. You challenged us. But we won. Go back to day 6 - summit day

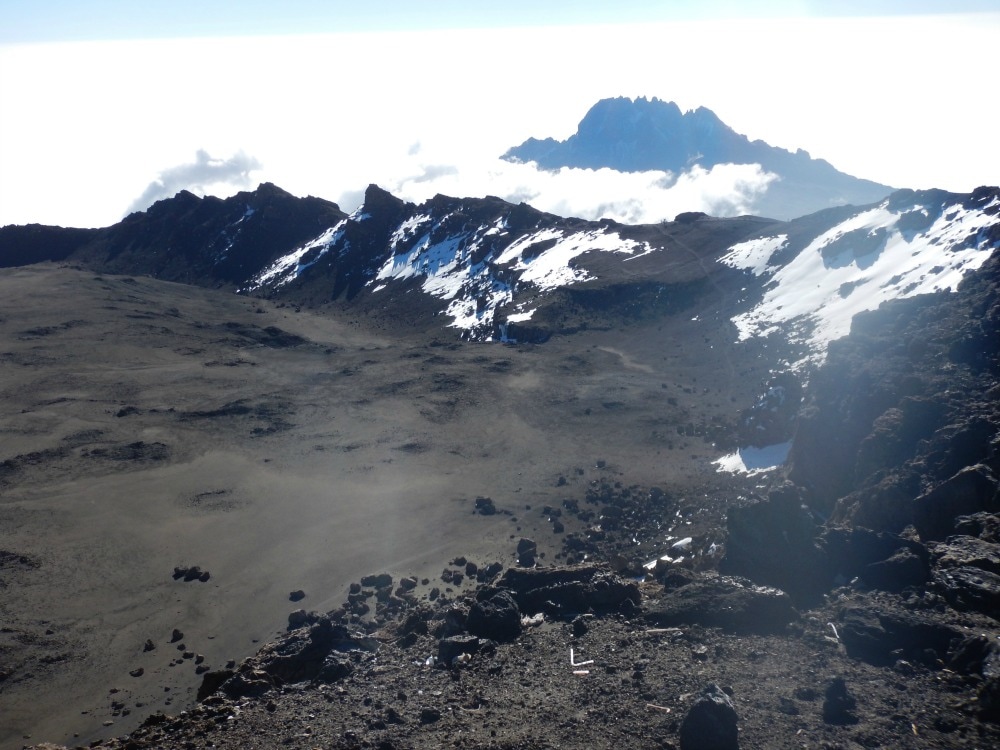

Read on about what happens to your body afterwards Join the Glamoraks community of women who love to walk, hike and have adventures. Start height: 4600m Midway height: 5895m End height: 3950m Looking like Michelin men, we waddled into the mess tent at 11pm for some ginger biscuits and porridge with heaps of sugar for energy. Nervous energy fizzed through the camp as people faffed with their water bottles, wondering whether 3 litres would be enough but unsure whether carrying more would be too much on such a tough climb (Tip: take at least five and ask a porter to carry it for you). Head torches were adjusted, hand warmers stuffed around water bottles, into boots and gloves, layers were added or removed. Finally at 11.45pm we set off, single file, pole pole. We were told that we would probably get hot during the first hour as it is steep, involves hauling yourself over some boulders and it’s not yet really too cold. They were right. But there was no way to remove layers, so zipping and unzipping became the order of the evening, not easy with bulky gloves on. The path became more even, a steady zig zag traversing the mountain, nine steps one way, nine steps back again. As we looked up, we could see a row of gently swaying lights like a magical lantern parade, weaving up and up and up. No matter how far back you tilted your head, the lights continued until eventually it was impossible to tell which lights were head torches and which were stars. We had a long, long way to go. As it grew colder, it became a mind game. Follow the boots in front of you. Listen to your music. Look out at the stars. Spot the southern cross. Look down at the far away lights of Moshi and Arusha miles and miles below. See the orange flashes of lightening storms in clouds far beneath us lighting up the sky like a Renaissance painting. One step. Another step. Breathe. Sip. Step. Breathe. Sip. Step. Take a moment to smile and revel in the awesomeness of where you are. Try to circle your neck, stiff from looking down. Try not to feel the three layers of waistband digging uncomfortably into your skin. Try to wriggle your toes to stop them freezing. Blow into your camelbak tube to stop the water in it freezing. Notice how the water you’re sipping turns into slush gradually, until eventually it freezes solid. Try to take the odd bite of an energy bar. Step. Breathe. Step. Breathe. For seven hours we did that, stopping only for an occasional pee break. Any last vestiges of modesty are well and truly thrown to the wind on summit night. You can step off the thin path to pee, but there is nowhere to go. You will find yourself squatting – as I did – next to several blokes standing alongside you peeing. You can choose to show your butt or your ‘front bottom’ to the passing traffic stream. As it’s dark and they’re looking at the boots in front of them, they probably won’t notice. But if they turn their head torch onto you, your naked glory will be caught in their beam. You genuinely will not care. You will be too busy trying to figure out how to pull all your layers back up before your butt freezes. At around 5am, the winds blew their hardest and coldest and it became increasingly difficult to hang onto any positive thoughts, which were driven away on the snow flurries. But soon thereafter we saw the first glow of dawn stretching in a pinky gold line along the curvature of the earth. It was magnificent and quite literally breath-taking, at such high altitude. That glimmer of light served as a tonic. We watched as the line of gold along the horizon grew, casting a strange bronze colour across the mountain face we were still traversing. At last the burning ball of a star that we call our sun popped its head over the horizon and instantly night was gone. To look down on a rising sun is a magical experience and unlike any other I’ve had. The euphoria of sunrise was short lived. We could now see the top of the mountain. Only the height of Snowdon left to climb, one person cheerily said…. The last push up the mountain to Stella Point is the toughest. Loose scree and dust, a steep gradient, very little oxygen and a path that never seems to end all start to take their toll on your good humour. My chest began to feel as though it had icy needles in it. For the first time, I allowed myself to think ‘what ifs’. What if this is pulmonary oedema? What if I can’t breathe? What if I don’t make it? I had been ignoring thoughts like these the entire trip, but when your reserves are low, it takes every ounce of your mental strength to push them aside and just keep walking. Every step takes an epic amount of effort, despite a painstakingly slow pace. Finally at about 8am we reached Stella Point at 5756m. A welcome cup of ginger tea helped revive me somewhat, but a walk to find a rock for a pee just about wiped about my final reserves. Looking along the rim of the crater, I could see Uhuru Peak in the distance. It was so close, yet it felt like an entirely different country. Gradually members of our group arrived at Stella in varying states of health. Some – like me – were tired, breathless and having to dig into deep energy reserves, but were nonetheless well. Others were less lucky, seriously battling to breathe, looking green after a night of relentless vomiting, staggering with dizziness and disorientation. We learned two of our group had had to turn back at 5300m, four couldn’t continue from Stella Point, and one was practically carried to Uhuru Peak and who we later learned had cerebral oedema. There wasn’t enough air to stand about, so we soldiered on to the final bit of the summit. It should be a gorgeous 45-minute walk with views over an ancient volcanic crater and carved glaciers glinting in the sunshine. But you don’t focus on that. You simply put one foot in front of the other in a determined effort to get to the top. At last, you reach the famous sign. There is no moment of jubilation. Well there wasn’t for me. Relief flooded through my body that I had at last reached the top. But that was it. My focus was simply to get my picture taken (it’s a bunfight up there as everyone wants to get their shot) and get the hell down so that I could release some of the tightness in my chest. After no more than 20 minutes at the top, I headed back to Stella Point. It was only at this point that I realised I still had to go down. Nine hours of walking and we were nowhere close to being done yet. They say that when you think you have spent all of your energy, you stilly have at least 40% in your reserve tanks. It was time to dig into those reserves. The path down hill is different to the one going up. No gentle zig zagging traverses, just a scree slope to slide down. This might be fun if you had any strength left in your legs, but there were few who did. The dust kicked up by the scree gets into your lungs and it takes a huge deal of concentration not to trip over hidden rocks. As you head down, the day heats up. All those layers you needed in the early hours of the morning are shed and added to your pack. The weight of your water, which you have now almost completely run out of, is replaced by the weight of your discarded clothes. Porters kindly took the daypacks of many. I wasn’t one of them. There are no words to describe this downhill, three-hour slog. You simply want to get back to camp. It became apparent why those people we’d spotted the day before weren’t smiling. Nobody prepares you for the down. Everyone is too busy thinking about summiting. But getting to the top is just half-way. You haven’t conquered Kili until you get to the bottom. I eventually staggered into camp around 12.30pm, having walked for just over 12 hours straight. I downed a litre of water, stripped off my boots and collapsed on my mattress, instantly falling into a deep sleep for an hour. I woke up coughing. The icy splinters I’d felt in my chest on the way up combined with the volcanic dust on the way down made for delightful grey sputum. Apparently it’s called the Khumbu cough, caused by low humidity and sub zero temperatures experienced at altitude and is thought to be triggered by over exertion. Tick, tick, tick. I was indeed a perfect Khumbu cough candidate. Lunch – our first proper meal since 5.30pm the night before – was an eclectic affair of pineapple, pancakes, vegetables and chips. But no-one cared. It was fuel. There wasn’t much conversation, just thousand mile stares and lots of coughing. Despite us all looking like extras from a zombie film set, we had to pack up our bags and carry on walking. There is no water at camp to replenish our stocks and certainly not enough oxygen to spend another night at Barafu. By 3.30pm we were back in our boots, trudging down the hill in fog. This path was however, a kind, gentle slope. Every step took us to more oxygen and strangely I felt stronger, rather than more tired the further I walked. The same can’t be said for some others who were feeling the exertions, particularly in their backs, knees and toes. Even with the extra oxygen, I was still ready to call it a day eventually.

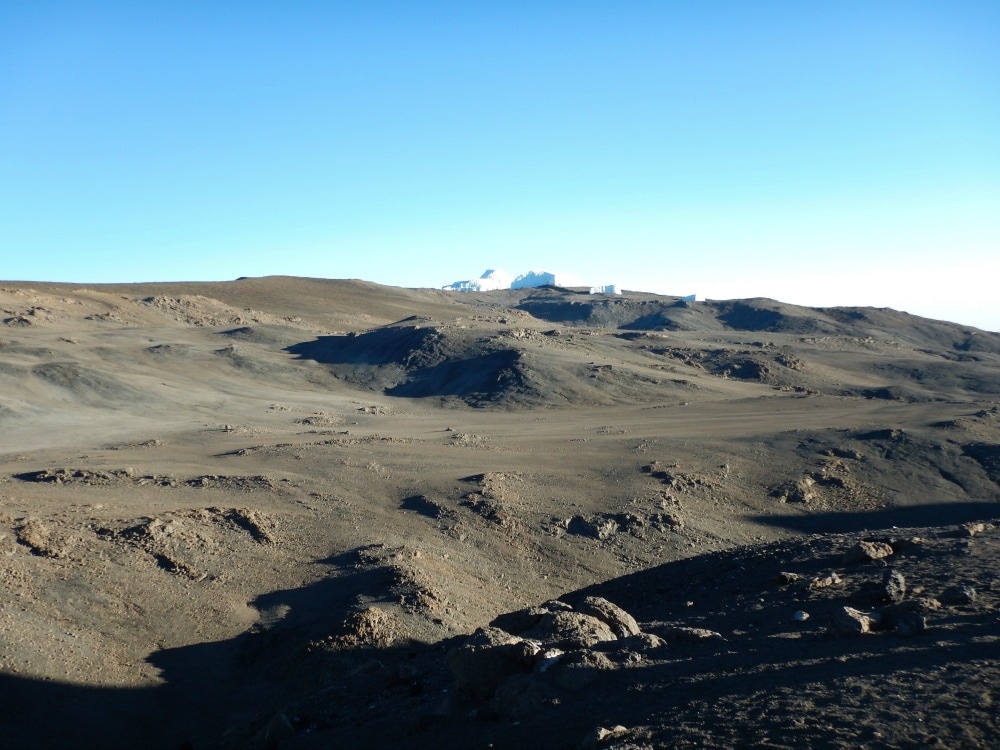

We arrived at High Camp at around 6.30pm, after what seemed like the longest day ever. Once again the porters had beaten us to it and served us ‘plain soup’, which tasted remarkably like all the other soups but still felt like liquid gold going down. Chicken and rice followed. I vaguely recall acting as mother for both mess tents as everyone sat staring blankly, unable to help themselves. We collapsed into bed. My sleep deprivation made me think that cleaning between my toes at this time was a good idea. It wasn’t. I gave up and passed out. The reality of what we had done drifted through my mind just as my eyes closed. We had summited Kilimanjaro! Thanks to my hot water bottle and the extreme exertions of the day, I actually slept the entire night without having to pee, my first time in a week. Start height: 3995m End height: 4600m I woke at 5am, listening to the sounds of the camp, before plugging in my audio book in an attempt to drift off again. I couldn’t. Although it was only Friday morning and we were only due to summit on Saturday morning, summit day would be starting on Friday night. We were in the final stretch. I assessed the hygiene levels of my smelly clothes, shrugged and opted for breakfast instead. The usual porridge greeted us along with a jazzy new addition of Vienna sausages stuffed with vegetables. Eating is hard work. There’s lots of passing of cups and plates. The chairs either list dangerously as they’re set on uneven ground or slope backwards, ready to tip you out the tent. Someone acts as mother to help everyone else from having to get up, slopping ladles of porridge into tin bowls. The pill popping commences. General discussions about how everyone is feeling do the rounds. And then it’s time to head out again for another day of walking. Standing on a rock, brushing my teeth before leaving, the clouds swirled around me, occasionally clearing to reveal the spectacular views. I was reminded of just how lucky I was to be doing this incredible challenge. It’s not glamorous. But it makes you feel alive. If you ignore the bustle behind you, it’s just you and the clouds on the top of the world. The walk was a short, but steep one through the strange alpine desert until it kindly levelled out for a while. Rocks, dust, stones that sound like shattering glass, a few scrubby plants and very little air kept us company as we walked. Despite the ever-thinning oxygen, it was a jovial walk full of banter and laughs as we tried to take our minds off any nasty side effects. Cheese jokes. Debates about Wookie genitalia and indeed whether Wookie’s were male or female. It kept us smiling all the way up the steep climb to base camp. We arrived at Barafu Camp, a barren, inhospitable place full of rocks and tiny patches of cleared ground for tents. Situated at 4600m, everything takes effort. Unpacking your sleeping bag, taking off your boots, trying to walk the 15 metres to the loo – it is all hard work that leaves you panting. I had yet another toilet disaster upon arrival. The toilet tents hadn’t been set up yet and there was nowhere even remotely private to pee, so I raced into my tent and grabbed my urinal (a spare given to me by a friend). I had used it effectively for the last two nights so had no qualms about using it now. Except I forgot about the pathetically weak plastic which had obviously reached the end of its life. Cue pee all over me, my clothes and the inside of the tent. When you have very little air to breathe, trying to mop up pee with wet wipes and change out of wet clothes is exhausting. Such fun. The weather at base camp is something out of the Book of Revelations. One minute it is so hot you can feel your skin frying. The next the clouds roll in, the winds blow and it is freezing. Hail is hurled down, thunder crashes below you and lightening zig zags the sky. It’s easy to believe you are losing your sanity. Lunch was pasta, veg and fresh pineapple washed down with a briefing talk that made all of us wish we hadn’t eaten. Our resident medic explained what would happen on summit night. We could expect to vomit, get raging headaches, suffer from hallucinations, battle to breathe and potentially suffer from High Altitude Cerebral or Pulmonary oedema. So that was comforting. We were also told to expect 25km winds, temperatures of -15c and up to 20cm of snow. We were advised to rest all afternoon. We didn’t need to be asked twice. Stumbling to our tents we noticed a stream of people who had obviously summited and were on their way down. Not one of them was smiling. Where was their elation and whooping and air punching? They looked like walking zombies. It didn’t bode well. After ‘sleeping’ through thunderstorms, snow showers and melt-your-face off heat for a couple of hours, we had an early dinner at 5.30 and were told to get to bed as we’d be woken up at 10.30pm. You try and sleep when you have a carnival of emotions jostling inside you... After zero sleep, we got up at the allotted time, got dressed into as many layers as we could and got ready to face the summit. Go back to day 4

Click here for day 6 - summit day Join the Glamoraks community of women who love to walk, hike and have adventures. Start height: 3900m End height: 3995m For the first time since the walk began, I couldn’t face a morning coffee, probably a symptom of the altitude. But the nausea passed after a breakfast of porridge (again!), scrambled egg, toast and pancakes. By 7.30am we were ready to begin the big climb, but first we took in the incredible views that showed us how high up we had come. We’d been warned about traffic on the Baranco wall as it’s a single file steep path up a rockface, with porters having to get by with their loads balancing on their heads. Thanks to our early start, we managed to get ahead of the bulk of the foot traffic and could simply concentrate on getting up. The wall looks a lot scarier than it is – as long as you don’t look down. It was a day to put poles away and use your hands to scramble over the boulders. Looking for a place to put your feet and gripping a hand hold was actually fun and certainly took everyone’s minds off feeling ill. However, there is one particular part that will get the hearts of those afraid of heights thumping. Called the Kissing Wall, you have to hug a rock and step across a gap with a good drop beneath it. A friendly guide waits with a hand outstretched to help you, but despite this, it still takes a deep breath and a leap of faith if you’re a vertigo sufferer like me. As I landed safely on the far side, it was though my body had to release the fear and adrenalin it had stored and I burst into inexplicable tears. I wasn’t the only one. Several of us all did the exact same. Altitude eh? It’s does funny things to your body and mind. After two hours of boulder scrambling straight up, we got to the top. A fellow vertigo sufferer and I had a big hug at the top, before moving as far from the edge as we could. Everyone amassed at the top, whooping that we’d conquered the wall and had a snack break and collective toilet visit behind the rocks. The mountain is littered with deposits from previous visits. You’ve always know when you’ve found a private toilet spot because of all the used tissue and piles of poo left behind. So you have a choice – privacy and revulsion, or a fresher spot where at least one person will be able to see you. By day 4, privacy was far less important than the ability to lean back against a rock with your backpack still on to use it as support both squatting down and getting up. The blokes had no idea how much easier they had it. Squatting multiple times a day with very little air to breathe is exhausting! Top tip: Do many squats as part of your training programme ladies. Suitably lightened, we set off along a long path we could see stretching ahead through a valley. The rain set in. It was about this time that I realised my waterproof jacket wasn’t actually waterproof anymore. We trudged on until our next campfire hove into view. Had we had wings, we could have flown across to it in minutes. Instead we had to traverse our way down the side of a steep valley that went on and on. Finally we crossed a stream on the valley floor and then had to head up the other side, which was just as steep, although mercifully shorter. As we lumbered up, the porters hopped like mountain goats up and down the path to fetch stream water for us to drink. Remarkable chaps. We arrived at Karanga camp, situated at 3995m. It was our last camp before base camp and walking up to the tents took supreme effort. The lack of oxygen could definitely be felt, with our wet clothes not adding to our joy. A hearty lunch of chicken, fried potatoes and greens, washed down with milo helped and we all set about trying to dry our kit in the brief snatches of sunshone. It’s hard to describe the intensity of the sun when it does come out at high altitude. It feels like a flame licking your skin and so our kit strewn across rocks and pegged on lines did dry. A handful of us headed out for another acclimatisation walk, a relentlessly uphill trek through alpine desert, giving us a taste of what was to come the next day. We headed back for dinner of cucumber soup, rice and vegetable sauce. Carb stodge is what you need. It’s warm and filling and certainly helped me have a better night’s sleep at last. We went to bed with the lights of Moshi every further away and the looming peak ever closer. Go back to day 3

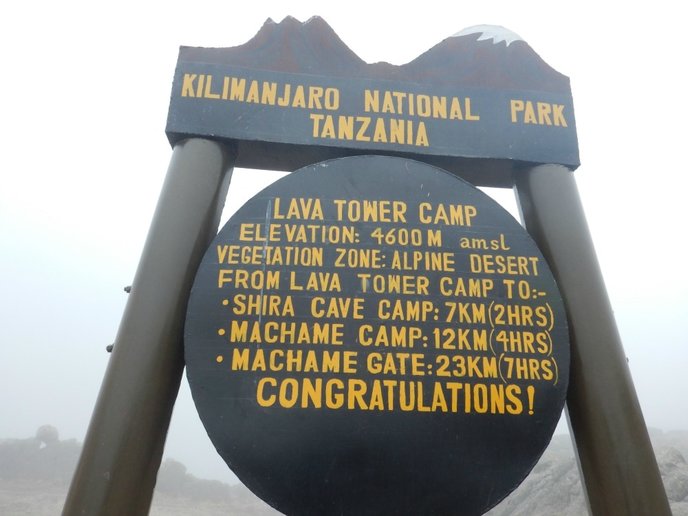

Read on about day 5 Join the Glamoraks community of women who love to walk, hike and have adventures. Start height: 3800m Midway height: 4600m End height: 3900m After a hideous night’s sleep thanks to my mattress not being fully inflated, which meant being cold and uncomfortable, I was keen to get up and out of the tent. I’d been told it was best to sleep with as little on as possible so that the sleeping bag fabric is next to your skin and can do its job, but I was so cold I ended up wearing about 4 layers including my coat. Top tip: inflate your mattress fully or better yet, hire one of the mattresses the tour company offers, which are thick and warm and cost just $15 and you don't have to fit it in your bag.. Adding to the drama of the night, my uriwell device broke. I’d just got the hang of using it properly when it experienced one concertina too many and snapped. My tent mate understandably shrieked as droplets sprayed the inside of the tent. They were water droplets as I’d rinsed it, but everyone in the other tents enjoyed the, ‘Oh my god, is that piss inside the tent!’ Every day is a laughing day.... Breakfast again at 6.30am due to a long day ahead. It featured porridge that made me gag due to altitude sickness, but which quickly made way for sausage, egg and toast, which I was happy to tuck into. Every breakfast time looked a lot like a drug addiction clinic, as everyone lined up their various tablets for the day ahead: Malarone, Diamox, pro-biotics, vitamins, ibuprofen, paracetamol, rehydration sachets. Then there was the sun lotion application, water bottle refilling and bag packing. By 7.30 we were on our way across the gorgeous Shira Plateau. Unlike the brutal ascent of the previous day, this was a gentle climb through alpine moorlands. We’d catch glimpses of the peak looming ahead of us, before the fog rolled in causing everyone to add layers and waterproofs. Despite the climb being more gradual, breathlessness became a common factor as we gained height. Pole pole, sippy sippy, pole pole, sippy sippy became a mantra in my head as I listened to my ipod. Music is an incredible mood alterer. One moment a toe tapping pop song would come on, making me want to move faster than the requisite pole pole. The next instant Elgar’s Nimrod would come on and I’d be moved to tears by the enormity of what we were doing. There is something incredible about listening to a beautiful piece of music, looking up at a snow covered peak or the clouds swirling around you and simply thinking: 'I am here!'. It’s moments like that, which make you forget about the discomfort. Mindset is such an important element in a walk like this. It is critical not to worry about what might happen or to dwell on how you are feeling. I found the best way to ignore any altitude side effects was simply to acknowledge them, congratulate my body for responding the way it was meant to, and then moved on. Complaining is a killer too. Focusing on the beauty around us and the once-in-a-lifetime privilege we had in doing the climb, helped keep my thinking positive. I concentrated hard on my breath, inhaling deeply through my nose and slowly expelling the air through my mouth. I’d sip regularly on my water, holding it in my mouth for a few seconds before swallowing it. I’d let the clouds and the music swirl around me and just enjoyed it. By lunchtime we’d made it to the famous Lava Tower, set at 4600m, another 1000m up from the last camp. The ever-awesome porters had raced ahead to set up the temporary lunch camp, cooked a fabulous lunch of pasta with chicken and made sure the toilets were ready for action! Fully fuelled up and ready to carry on what was expected to be a 10-hour walking day in total, we left the eerie tower looming in the fog behind us as we descended down a steep rocky section into a valley, across a stream and then up again. Over the crest of that hill we made our way down again following a stream and walking through strange otherworldly trees that were apparently over 90 years old and which never lost their leaves. I loved this walk and descending to a lower altitude made it easier to breathe. At last we arrived at the beautiful Baranco Camp situated at 3900m. It had views all the way down to Moshi in one direction and views up to the snow-covered summit in the other. It was, however, hard to ignore the wall of rock that stood between us and that end point. We’d be tackling the Baranco Wall the next day and for a vertigo sufferer, it didn’t look terribly appealing. We had a flat pitch – yay! – no rolling into my tent mate in the middle of the night. I also got a washy washy wash and changed my clothes for the first time in three days. Whoop! Clothes up till this point had involved layers – thin walking trousers, t-shirt, thin midlayer, fleece gilet, waterproof outers and the option to switch between sunhat and fleece beanie. While walking you get warm. The minute you stop, you feel the cold. Good sunglasses, hand sanitiser, lip balm and tissues are other essentials to have on you at all times. After getting clean, it was dinnertime. A treat of popcorn and mugs of tea served as an appetiser, before the main event arrived. Delicious leek soup with bhajis (or what could be described as savoury donuts) was followed with rice and mash with vegetable sauce. A warming mug of milo helped us to brace for the cold dash to the tents. I used two mattresses, had a water bottle filled with boiling water to serve as a hot water bottle, attempted the naked sleeping thing, followed by layers of clothes. I was still cold and the altitude made it feel as though someone was sitting on my chest. So a restless night followed. I began to give up on ever sleeping well. Day 4 and the Wall awaited. Go back to day 2

Read on about day 4 Join the Glamoraks community of women who love to walk, hike and have adventures. Start height: 2800m End height: 3800m ‘Hello. Good morning. Coffee?’ a little voice said outside my tent. I glanced at my watch. 6am. I’d been semi-awake for at least an hour listening to the sounds of porters making breakfast. Unzipping a tent was the lovely man who would bring coffee, tea or milo to our tents every morning to start our day with a smile. Getting a coffee, I began the repacking process, trying to figure out how many layers I’d need. Although it’s cold in the morning and evenings, the day heats up, particularly as you hike up steep bits. Many thin layers is the answer. I got some more washy washy water and attempted to clean my hands and face, using my mini Molten Brown bottle of soap, sponge and nailbrush, all of which had been recommended as a way to make you feel more human. It does help clear some of the grime, but it’s an exercise in futility. The minute you’re clean, you have to tie dusty bootlaces or sort out muddy poles. It is far easier to use wet wipes regularly and hand sanitiser even more often. We headed to breakfast and got to experience our first porridge. I cannot praise the chefs enough on their ability to cook for that many people on just a camp stove, but I found the porridge hard to face. Every morning it varied in consistency. Day 1 was the runniest. Day 7 they seemed to have nailed it, or perhaps we’d just got used to it. The trick to making it edible was lots of sugar. I’m talking equal parts sugar to porridge. Bread with peanut butter, pieces of omelette and Vienna sausages made up the smorgasbord. After a bit of waiting around for water – the only time on the entire trip where we had a water glitch (another incredible job performed by the porters) – we set off. Or should I say up. Almost immediately we began a steep uphill climb. Unlike day one, which had featured a tree covered path, with a few slightly steep bits, day 2 was determined to let you know that you were climbing a mountain. Boulders, slippery rocks, expansive views, blazing sunshine, and scrambling using your hands, all got our hearts pumping. One of our group had a nasty slip and banged her head and eye, but made of sheer grit, she continued on, sporting a shiner. Although technically a lot more difficult and steeper than the previous day, most people seemed to enjoy it more, thanks to the variety of the path. The lush rainforest had been replaced with alpine vegetation including trees covered in long, yellow lichen, which would have made an excellent substitute for Trump’s hair. Weird pineapple-shaped trees, caves and rock pools all added to the feeling that we were walking on the set of Jurassic Park. The effects of the hard climb and altitude started to take effect, with some of our group starting to feel ill, breathless or headachey. For my part, I felt a dull pressure, rather than pain, in my head and occasionally felt a bit breathless. But that could have been caused by the steep climb. While we stopped to catch our breath, the porters charged past with their heavy loads. Much of the day was spent yelling, ‘Porters coming through, step to your left.’ Traffic is something you have to contend with on Kilimanjaro. It’s not like taking a hike through the empty wilds of Yorkshire. Every group has hundreds of porters and there many different groups all going up at the same time, some walking at a faster pace than others. Looking at the people around me, I decided to take a pre-emptive Diamox as a preventative to altitude sickness. I didn’t feel bad and was genuinely enjoying the walk, but altitude is a funny thing. You never know when it might affect you. At last we reached the ridgeline. The path flattened out and the sun came out, making it easy to burn unless you’re covered in factor 50 cream. The clouds bubbled below us leaving us to bake in the rays. We got to Shira Camp early afternoon. After lunch, tent sorting and a brief nap, it was time for an acclimatisation walk. This optional short hour-long walk takes you up another few hundred metres, just to get you used to less oxygen. It supposedly makes you sleep better when you go back down again. Arriving back at camp, the porters all gave us a welcome sing and dance. Lots of ogi ogi ogi, oy oy oy chanting followed the famous Jambo Bwana song. We got introduced to all the team and their respective roles. Maximum Respect (the group’s motto) was given to the toilet technicians, whose job it is to empty the little loos into the long drops. It’s incredible how much energy the porters have. They’d lugged all the kit up the steep slopes all day, set up all the tents, cooked our meals, set up the loos and prepared the water – yet they still had boundless energy to dance and sing and smile. In contrast, many of our group were now feeling the effects of altitude sickness. Vomiting, dizziness, headaches, emotional meltdowns, breathlessness, nausea, and exhaustion all seemed to be cropping up. I felt slightly breathless, slightly headachy and felt the odd bit of dizziness, but mostly felt fine….until I visited one of the loos after someone else had been in there! That brought on nausea fairly fast. Mostly, it felt like a cross between a hangover and morning sickness. Dinner, for those who could manage it, was zucchini soup, followed by rice with spinach and okra stew, with skewers of some kind of meat (possibly goat?). It also happened to be the birthday of one of our team. The incredible chefs had outdone themselves by baking a sponge cake Mary Berry would have been proud of. How they did it on a camp stove remains a mystery. Then time for bed. We’d reached 3800m, another 1000m in height gained. It was getting a lot colder at night and it didn’t take much convincing to get people to settle down fast. Read day 1. Read day 3. Join the Glamoraks community of women who love to walk, hike and have adventures. Start height: 1800m End height: 2800m We stood waiting at Machame gate while paperwork was sorted. The excitement and tension was palpable as people filled water bottles, took pictures and visited the loos countless times. All those months of preparation, training and fund raising had at last led us to The Big Day. I'd actually left home three days before, travelling from York to Reading by train, spending a night with the friends I'd be climbing with, catching a plane to Nairobi the next day, spending a night in a less than luxurious hotel, catching a tiny plane from Nairobi Wilson airport to Kilimanjaro airport, driving along bumpy roads to our Kilimanjaro hotel, getting a briefing, repacking bags, seeing the mountain free of clouds for the first time and gulping at how far up it went, trying to ignore the revelry of a group who had just completed their summit, attempting sleep (impossible) in the last comfortable bed we'd have for a while and finally getting to the gate the next morning. As we waited, we watched scores of porters loading themselves up with huge mounds of kit, balancing it on their heads or shoulders and marching off up the hill. It was a never-ending stream of people, like busy ants working as a team. Finally at about 11.30am we were ready to go. We passed by the starting point sign and immediately began to walk uphill. After days of sitting around, the uphill climb at an already high altitude of 1800 metres immediately made hearts pound and breath quicken, but after the blood got moving and we got into a pole pole (slowly slowly) rhythm, things calmed down and we could appreciate our surroundings. Almost of all of day 1 is a long, slow 11km walk through lush rainforest. It's hot, humid and in a few places steep. But mostly it is easy walking on a good path. We were lucky enough to spot columbus monkeys in the distance and only had to contend with a short rain shower. T-shirts and shorts are a good choice of kit, but don't forget bug spray and sunblock. During the walk we stopped to meet our guides, experienced the long drop toilets and decided that bush pees were a better alternative. Almost immediately, the hand sanitising gel that had been recommended came into use. After a couple of hours, we stopped for a lunch break. We'd been given a packed lunch in an old-fashioned style lunch box. Fried chicken and a beef pasty were the stars of the show, but there was plenty to fuel us so that we could continue our uphill climb. Although 11km really isn't a long walk, as a leg warmer it certainly felt long enough as we made our way into Machame Camp at 2800m, our first campsite of the trip. The site was a bit of a shock to the system. Cramped and overflowing with tents, rocky and muddy ground, and fairly whiffy toilets all brought the reality of the challenge into sharp focus. It felt like a refugee camp and for anyone who hadn’t quite thought through the realities of sleeping in a tent with fairly basic facilities, it was a short, sharp shock. We had to find our tents and commence what would become (but wasn't yet) a well practised procedure of inflating mattresses, unrolling sleeping bags, attempting to use the washy washy water to clean off the grime of the day and head to the mess tents for dinner. It is remarkable what the chefs can create in very basic conditions. While some might find the food basic, it was always tasty. Salty and very peppery pumpkin soup was followed by pasta with vegetable sauce and fresh mango. I didn't fancy eating much. The excitement of the day, following by a lot of uphill walking, a dash of stress at trying to sort out my bed for the night with a mattress that kept deflating, and the first prickles of altitude sickness all meant food didn't hold much appeal. But a hot cup of milo was a warming comfort. Bedtime on the mountain is early. By 8.30pm you are tucked up in your sleeping bag. I found listening to an audio book the easiest way to send me off to sleep. Earplugs and an eye mask help to block out the sounds of tent zips being unzipped as people head out to the loo and head torches flashing through your tent. You can hear everything that happens in other tents - snoring, farting, chatting or giggling. On the mountain, privacy isn't really an option.

Speaking of privacy, let's touch on a subject that became central to my Kili climb. Peeing. When you drink 4 to 6 litres of water a day (which you need to do to help reduce the effects of altitude) and if you take Diamox (a diuretic) you will need to pee a lot. While you're out walking, this becomes a bush pee (more on those in future blog posts). But at night it is more of a challenge. You don't want to have to get out of your warm sleeping bag, head out into the cold and stumble over rocks to find a loo in the dark. If you're in a tent on your own, it's easy enough to use a shewee/bottle combo or peebol to pee into. But when you're sharing you need to be a bit more discreet. I had discovered what I thought was a brilliant device - a uriwell unisex urinal. The concertina body extends to hold up to a litre of pee and you can use it in a semi reclined position inside your sleeping bag. It takes a good amount of confidence to let that first pee go, hoping that you don't miss or spill. But they do work. Up to two times. Thereafter, the plastic snaps.....something I didn't realise....more on that later…. So day 1 drew to a close. We'd climbed 1000m in about 5 hours of slow walking, experienced camp life and our first mess tent meal, tackled long drops, bush pees and in-tent urination. Day 2 awaited. Read Day Two. Read what to pack for Kilimanjaro. Read how to prepare for Kilimanjaro. Packing for Kilimanjaro is no mean feat. You need enough stuff to span hot, humid temperatures all the way through to sub-zero, freeze your face off stuff, plus the possibility of a lot of rain. On top of this, you need to take a lot of miscellaneous stuff - what feels like a full medical cabinet and plenty of snacks. All of this adds to the weight. And the weight thing gets complicated. Your packing skills become a balance between how much things weigh versus their necessity. So I have created this blog post and video to help you with your packing. I have done this before I have actually climbed Kilimanjaro, so there may be things I've packed that are completely superfluous and there may be other things I really should have more of. But this is my best guess as to what I will need. I hope you find it helpful. Let's start: You need two bags: your backpack and your duffel bag. The porters will carry your duffel bag up the mountain for you and it mustn't weight more than 15kg. Your backpack will be your hand luggage for your flight/s, your duffel bag goes in the hold. If you are connecting from Nairobi Wilson Airport to Kilimanjaro Airport, you may be limited to just 15kg for all of your luggage combined for that flight. That is pretty tough going given how much stuff you need. In addition, you may have a third bag with spare clothes for the safari afterwards that you will leave behind at your hotel before you climb up. Weight for that needs to be factored in too. My stuff will be over the 15kg airline allowance by about 6kgs.... Some bag related considerations:

I've probably got too many socks (but I'm paranoid about keeping my feet dry and warm and comfortable) and my big worry is whether I will be warm enough on summit night, but I've gone for many layers rather than one big coat as I typically get too hot when I walk. Beneath the video, I have created a packing list including what I intend to wear on summit night. What I plan on wearing on summit night

What I have packed Note that everything has been packed into dry bags in the following groups: Sleep sack I've put all of this into one bag so that when we arrive in camp, it's simple to set up my bed with everything I need for the night.

Clothes sack

Underwear sack

Hats & gloves sack

Washbag

Medical bag

Separate mini medical kit for daypack

In backpack

Safari bag

Miscellaneous

A year ago my good friend Rona sent me an email from the Thames Valley Air Ambulance with details of a fundraising challenge: to climb Kilimanjaro. 'Wanna do it?' she asked. 'Sure,' I said. It's easy to say yes to something when it's over a year away and you haven't really researched what is involved.

It was about 6 months after signing up that I thought perhaps I should look into what climbing Kilimanjaro involved. In my head it was a big hill. How hard could it be? Apparently quite hard. Suddenly, to quote some American gangsta, 'Shit got real.' Turns out Kilimanjaro is actually 5,895 metres high. It's the world's highest freestanding mountain. In terms of altitude, its peak sits at the top end of the extreme altitude category and just below the 'Death Zone' category. So that was comforting. I decided it was time to get a bit more organised about this expedition. I wrote a list of what I needed to get sorted or learn more about:

Training How do you train to climb up a very steep mountain when you live in one of the flattest places in the country? I had a session with a personal trainer who gave me exercises that focused on my butt, quads and calves. I sort of did those (a bit - probably should have done more of them). I went walking with increasing regularity and added weight to my pack. I borrowed an elevation training mask from a friend and climbed Sutton Bank (the one hill near me) in an attempt to recreate the lack of oxygen I'll have on Kilimanjaro. I joined a gym and spent time on the cross trainer. But not as much as I should have due to a miserable series of cold and flu. And I climbed the Yorkshire Three Peaks as a final bit of hill action. Do I feel as fit as I should be? No. Will I manage? I hope so. Kit This was what kept me awake at night. How do you pack for a walk that starts in 30C heat and ends in temperatures around -20C? And it needs to be waterproof and insulated and lightweight as you're only allowed a maximum of 15kg. Just when you think you have everything someone tells you not to forget spare batteries or a head torch or hand warmers or knee supports. I feel as though I have a permanent post-it pad being scribbled on in my brain. I have borrowed a huge amount of kit from a friend who did it last year, but have also spent a small fortune on new stuff. I will do a separate post on kit because there is so much to cover. Suffice to say, you will spend an inordinate amount of time (and money) in outdoor shops fondling goretex. As for packing, it takes serious skills and thought to pack everything you need into a small space that is still convenient. You will spend HOURS attempting different packing techniques and will eventually come to the conclusion that two pairs of knickers for a week is fine. Passport and visas I had to renew my passport as you need to have at least 6 months left on your passport to travel. Then you need a visa for Tanzania, which is simple enough to get by downloading the form off the Tanzanian's embassy's website and posting it off. It costs £40. But timing is critical. If you send it off too far in advance, it will be out of date. If you don't send it off early enough, you risk not getting it back in time. Aim for 6 weeks before departure date. We also need transit visas for Kenya as we are spending over 12 hours there. You can get these here online. You will need a transit visa for the way there and the way back. It costs $20 each way. Vaccinations You need to get to a travel health clinic to find out what vaccinations you need. You will get conflicting information. In short, if you are travelling to Tanzania via a Yellow Fever country (like Kenya) you need a Yellow Fever Vaccination certificate. Other jabs you should get are Hep B, not available on the NHS and cost £42 each, unless you get them combined with Hep A (but you won't be able to get that if you've already had the Hep A jab at some point in the past). I also got Typhoid and the combined Diptheria, Tetanus and Polio jab, which are given free on the NHS. Be sure to get these done well in advance. Fundraising You can climb Kilimanjaro without raising money for a cause. But many of the treks are arranged by charities. I am raising money for the Thames Valley Air Ambulance Service. You can donate here. This takes a good deal of effort. It's not fun asking friends and family for money. It's even harder to do it when the charity you're supporting isn't in the local area you live in. But it's worth doing and serves as a motivator to keep going. There are many ways you can raise funds - from holding events, raffles and holding collection buckets. Or you can just email all your friends and do shout outs on social media. All of this takes time and effort. Itineraries, flights and money Your tour operator will probably arrange your flights for you, but we opted to use airmiles and booked our own. If you're heading to Africa and gorgeous Tanzania, then you'd be mad not to add a safari to your trip. We had the option of using our expedition organiser's add on safari, but as we had inside contacts, we arranged our own. But you need to factor all of the travel time and logistics into your planning. You also need to account for the extra dosh this will cost you, including the tips for the porters on the hike and the safari guides. I will be taking $500 with me in the hope that this covers what I need. But my point is, when you're doing your sums, this is another financial thing to factor in and it has to be on your dime. It's entirely separate from any fundraising you do. Insurance It's always comforting when you need to take out special insurance to cover you for hiking up to 6,000 metres with helicopter evacuation....But that's what you need. Luckily my travel insurance does cover me for that but it took many calls for me to confirm that I was DEFINITELY covered for this. Childcare If, like me, you are a mother and have children who are going to need looking after while you're off having your Kilimanjaro adventure, you are going to need to arrange childcare. It's not easy if you don't have grandparents around to help or a partner who can adapt their work to fit around school hours and kids. But if you want to do it, you will make a plan. Just remember to factor in the additional costs for any additional childcare costs you have to pay for. Also, don't worry about the kids being heartbroken without you there. THEY WILL BE FINE. Please believe me. You are setting an example to them that life is about living and having adventures, so please don't beat yourself up about this. Medication and health Who would have thought that a 7 day hike up a hill could require quite so much thinking about health. You will need anti-malarials. You may want to get Diamox, a drug that helps with altitude sickness. You probably want to start taking probiotics to help your gut deal with unusual food and water. Vitamins and gingseng to give you a boost will help too. If you're a woman, you will want to give thought to how you manage your periods while you're up the mountain. Get a coil fitted many months in advance, take a tablet to stop the bleeding, work out which sanitary product is going to be least inconvenient to use should it happen. You will also need to consider what you do about having to pee countless times during the night. I suggest one of these. Altitude sickness I've listed this separately from the rest of health because it is the thing that will wake you up at night in a panic. The distances you cover every day in Kilimanjaro aren't long. And yes it is all up hill (or downhill at the end) and yes you are sleeping in a tent and using very basic toilet facilities. But all of that doesn't really register on the fear scale. It's the fact that we will be going somewhere that has far less oxygen than our bodies are used to that terrifies me. I've listened to plenty of advice: walk slowly, drink a lot, keep eating, take Diamox if you need it (but only in the morning otherwise you'll pee even more), take paracetamol. Expect to have a headache. Expect nausea. I now fully expect that I will at some point feel awful. I just really don't want to get the severe version of it - High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema (HAPO) or High Altitude Cerebral Oedema (HACO). You can read up more about it here. Bottom line: there is nothing you can do about it. If you're affected, you're affected. Walk slowly, drink and hopefully all will be fine. So if you are thinking about climbing Kilimanjaro, just be aware that there is a lot of work to do before you even take your first step. I have been told that summit night is the most challenging thing - both physically and mentally - you will ever do. Getting to this point feels as though it has been a challenge in itself. But that was never going to stop me. Life is about pushing yourself out of your comfort zone and doing things that may be uncomfortable at the time, but will be the memories you treasure most. So go for it. Join the Glamoraks community of women who love to walk, hike and have adventures. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Get social. Follow us.

|

Don't get left out.

Add your email to be alerted about any Glamorak events, walks, get togethers, challenges or news.

Success! Now check your email to confirm your subscription.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed