|

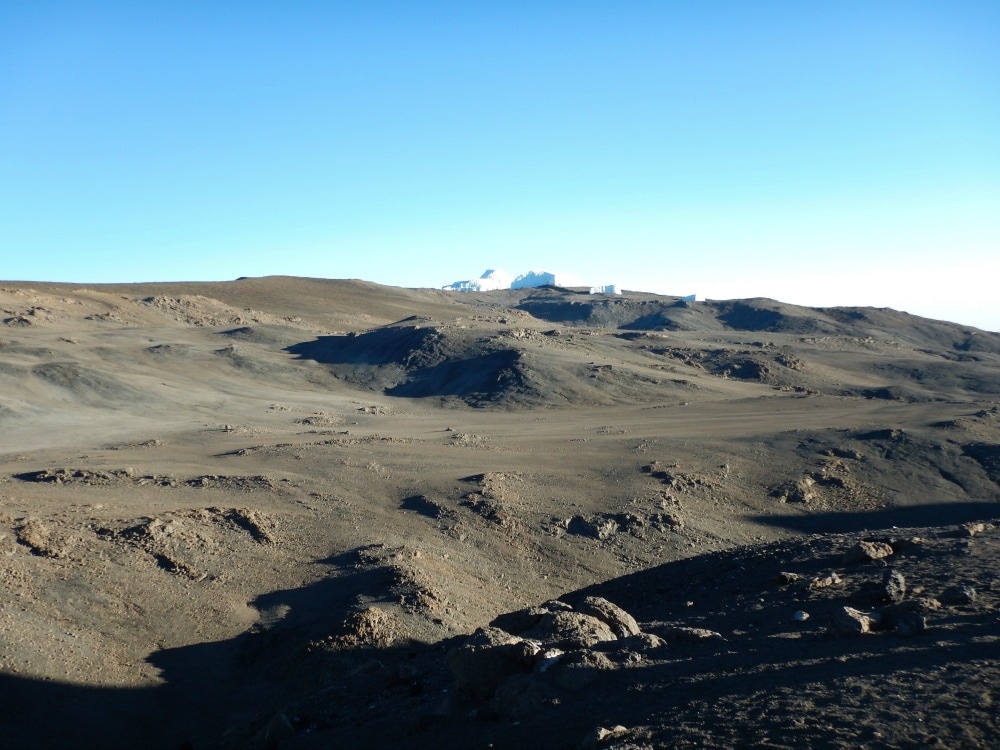

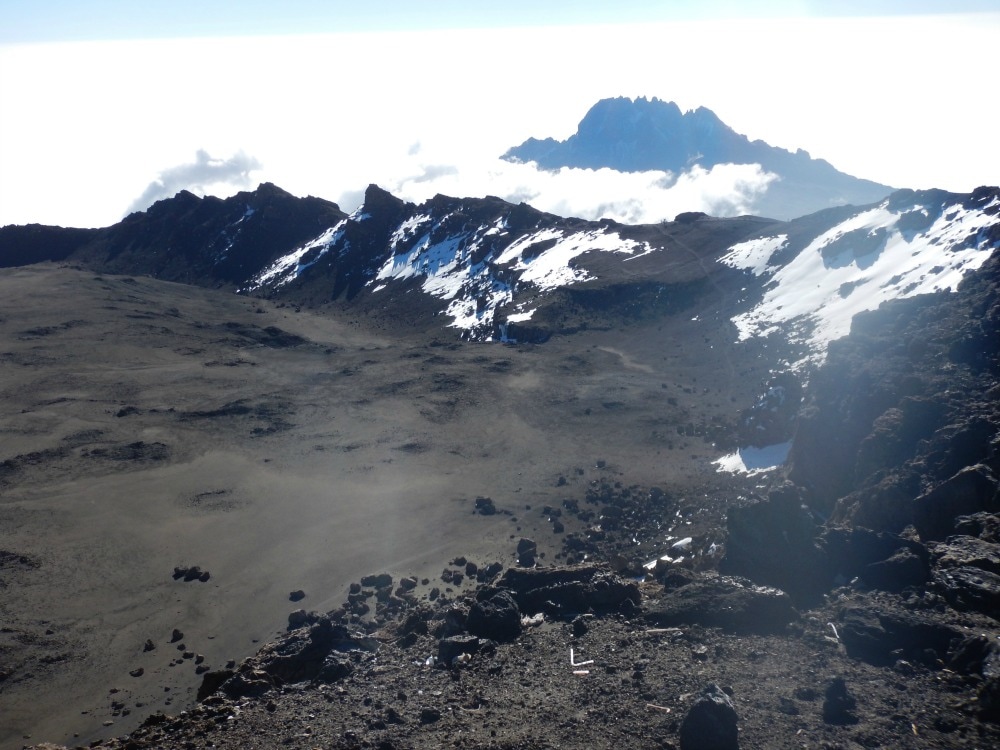

Start height: 4600m Midway height: 5895m End height: 3950m Looking like Michelin men, we waddled into the mess tent at 11pm for some ginger biscuits and porridge with heaps of sugar for energy. Nervous energy fizzed through the camp as people faffed with their water bottles, wondering whether 3 litres would be enough but unsure whether carrying more would be too much on such a tough climb (Tip: take at least five and ask a porter to carry it for you). Head torches were adjusted, hand warmers stuffed around water bottles, into boots and gloves, layers were added or removed. Finally at 11.45pm we set off, single file, pole pole. We were told that we would probably get hot during the first hour as it is steep, involves hauling yourself over some boulders and it’s not yet really too cold. They were right. But there was no way to remove layers, so zipping and unzipping became the order of the evening, not easy with bulky gloves on. The path became more even, a steady zig zag traversing the mountain, nine steps one way, nine steps back again. As we looked up, we could see a row of gently swaying lights like a magical lantern parade, weaving up and up and up. No matter how far back you tilted your head, the lights continued until eventually it was impossible to tell which lights were head torches and which were stars. We had a long, long way to go. As it grew colder, it became a mind game. Follow the boots in front of you. Listen to your music. Look out at the stars. Spot the southern cross. Look down at the far away lights of Moshi and Arusha miles and miles below. See the orange flashes of lightening storms in clouds far beneath us lighting up the sky like a Renaissance painting. One step. Another step. Breathe. Sip. Step. Breathe. Sip. Step. Take a moment to smile and revel in the awesomeness of where you are. Try to circle your neck, stiff from looking down. Try not to feel the three layers of waistband digging uncomfortably into your skin. Try to wriggle your toes to stop them freezing. Blow into your camelbak tube to stop the water in it freezing. Notice how the water you’re sipping turns into slush gradually, until eventually it freezes solid. Try to take the odd bite of an energy bar. Step. Breathe. Step. Breathe. For seven hours we did that, stopping only for an occasional pee break. Any last vestiges of modesty are well and truly thrown to the wind on summit night. You can step off the thin path to pee, but there is nowhere to go. You will find yourself squatting – as I did – next to several blokes standing alongside you peeing. You can choose to show your butt or your ‘front bottom’ to the passing traffic stream. As it’s dark and they’re looking at the boots in front of them, they probably won’t notice. But if they turn their head torch onto you, your naked glory will be caught in their beam. You genuinely will not care. You will be too busy trying to figure out how to pull all your layers back up before your butt freezes. At around 5am, the winds blew their hardest and coldest and it became increasingly difficult to hang onto any positive thoughts, which were driven away on the snow flurries. But soon thereafter we saw the first glow of dawn stretching in a pinky gold line along the curvature of the earth. It was magnificent and quite literally breath-taking, at such high altitude. That glimmer of light served as a tonic. We watched as the line of gold along the horizon grew, casting a strange bronze colour across the mountain face we were still traversing. At last the burning ball of a star that we call our sun popped its head over the horizon and instantly night was gone. To look down on a rising sun is a magical experience and unlike any other I’ve had. The euphoria of sunrise was short lived. We could now see the top of the mountain. Only the height of Snowdon left to climb, one person cheerily said…. The last push up the mountain to Stella Point is the toughest. Loose scree and dust, a steep gradient, very little oxygen and a path that never seems to end all start to take their toll on your good humour. My chest began to feel as though it had icy needles in it. For the first time, I allowed myself to think ‘what ifs’. What if this is pulmonary oedema? What if I can’t breathe? What if I don’t make it? I had been ignoring thoughts like these the entire trip, but when your reserves are low, it takes every ounce of your mental strength to push them aside and just keep walking. Every step takes an epic amount of effort, despite a painstakingly slow pace. Finally at about 8am we reached Stella Point at 5756m. A welcome cup of ginger tea helped revive me somewhat, but a walk to find a rock for a pee just about wiped about my final reserves. Looking along the rim of the crater, I could see Uhuru Peak in the distance. It was so close, yet it felt like an entirely different country. Gradually members of our group arrived at Stella in varying states of health. Some – like me – were tired, breathless and having to dig into deep energy reserves, but were nonetheless well. Others were less lucky, seriously battling to breathe, looking green after a night of relentless vomiting, staggering with dizziness and disorientation. We learned two of our group had had to turn back at 5300m, four couldn’t continue from Stella Point, and one was practically carried to Uhuru Peak and who we later learned had cerebral oedema. There wasn’t enough air to stand about, so we soldiered on to the final bit of the summit. It should be a gorgeous 45-minute walk with views over an ancient volcanic crater and carved glaciers glinting in the sunshine. But you don’t focus on that. You simply put one foot in front of the other in a determined effort to get to the top. At last, you reach the famous sign. There is no moment of jubilation. Well there wasn’t for me. Relief flooded through my body that I had at last reached the top. But that was it. My focus was simply to get my picture taken (it’s a bunfight up there as everyone wants to get their shot) and get the hell down so that I could release some of the tightness in my chest. After no more than 20 minutes at the top, I headed back to Stella Point. It was only at this point that I realised I still had to go down. Nine hours of walking and we were nowhere close to being done yet. They say that when you think you have spent all of your energy, you stilly have at least 40% in your reserve tanks. It was time to dig into those reserves. The path down hill is different to the one going up. No gentle zig zagging traverses, just a scree slope to slide down. This might be fun if you had any strength left in your legs, but there were few who did. The dust kicked up by the scree gets into your lungs and it takes a huge deal of concentration not to trip over hidden rocks. As you head down, the day heats up. All those layers you needed in the early hours of the morning are shed and added to your pack. The weight of your water, which you have now almost completely run out of, is replaced by the weight of your discarded clothes. Porters kindly took the daypacks of many. I wasn’t one of them. There are no words to describe this downhill, three-hour slog. You simply want to get back to camp. It became apparent why those people we’d spotted the day before weren’t smiling. Nobody prepares you for the down. Everyone is too busy thinking about summiting. But getting to the top is just half-way. You haven’t conquered Kili until you get to the bottom. I eventually staggered into camp around 12.30pm, having walked for just over 12 hours straight. I downed a litre of water, stripped off my boots and collapsed on my mattress, instantly falling into a deep sleep for an hour. I woke up coughing. The icy splinters I’d felt in my chest on the way up combined with the volcanic dust on the way down made for delightful grey sputum. Apparently it’s called the Khumbu cough, caused by low humidity and sub zero temperatures experienced at altitude and is thought to be triggered by over exertion. Tick, tick, tick. I was indeed a perfect Khumbu cough candidate. Lunch – our first proper meal since 5.30pm the night before – was an eclectic affair of pineapple, pancakes, vegetables and chips. But no-one cared. It was fuel. There wasn’t much conversation, just thousand mile stares and lots of coughing. Despite us all looking like extras from a zombie film set, we had to pack up our bags and carry on walking. There is no water at camp to replenish our stocks and certainly not enough oxygen to spend another night at Barafu. By 3.30pm we were back in our boots, trudging down the hill in fog. This path was however, a kind, gentle slope. Every step took us to more oxygen and strangely I felt stronger, rather than more tired the further I walked. The same can’t be said for some others who were feeling the exertions, particularly in their backs, knees and toes. Even with the extra oxygen, I was still ready to call it a day eventually.

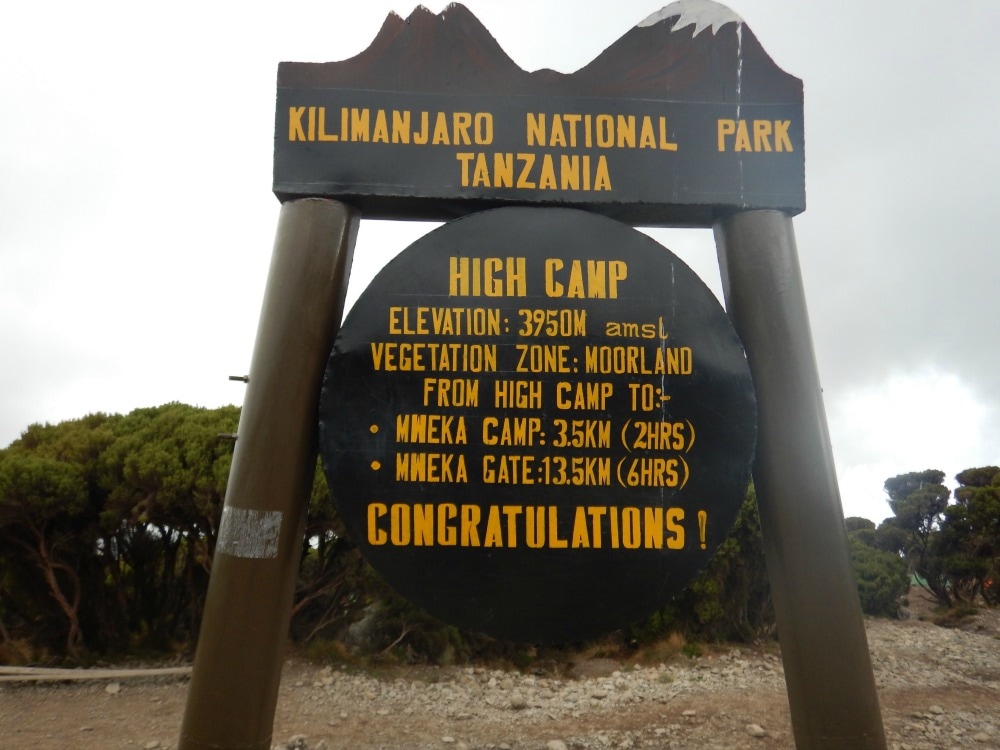

We arrived at High Camp at around 6.30pm, after what seemed like the longest day ever. Once again the porters had beaten us to it and served us ‘plain soup’, which tasted remarkably like all the other soups but still felt like liquid gold going down. Chicken and rice followed. I vaguely recall acting as mother for both mess tents as everyone sat staring blankly, unable to help themselves. We collapsed into bed. My sleep deprivation made me think that cleaning between my toes at this time was a good idea. It wasn’t. I gave up and passed out. The reality of what we had done drifted through my mind just as my eyes closed. We had summited Kilimanjaro! Thanks to my hot water bottle and the extreme exertions of the day, I actually slept the entire night without having to pee, my first time in a week.

2 Comments

Jackie erpen

14/6/2018 07:46:43 am

What an achievement - very well done. So glad you are all safe....fantastic

Reply

Alison

13/7/2019 06:59:08 am

Thanks for this. My daughter and husband will arrive at Barafu today, and your piece has helped me understand what they’ll be experiencing. I’m here in the comfort of home rooting for them!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Get social. Follow us.

|

Don't get left out.

Add your email to be alerted about any Glamorak events, walks, get togethers, challenges or news.

Success! Now check your email to confirm your subscription.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed